American Eel

Life History

American eel (Anguilla rostrata) are a catadromous fish species, spending most of their life in freshwater or estuarine environments, traveling to the ocean as adults to reproduce and die. Sexually maturing eel migrate to spawning grounds located in the Sargasso Sea, a large portion of the western Atlantic Ocean east of the Bahamas and south of Bermuda. American eel are a panmictic stock, meaning that individuals from the entire range come together to reproduce. American eel found along the eastern coast of Mexico are from the same population as eel found in the St. Lawrence River in Canada.

American eel develop over several life stages: leptocephali, glass eel (also known as elvers), yellow eel, and silver eel. Yellow eel are the primary life stage harvested by commercial and recreational fishermen.

In August 2018, a Symposium on American Eel titled, "Aristole's Mud to Modern Day: What Do We Actually Know About Catadromous Eels?" was held at the American Fisheries Society's Annual Meeting in Atlantic City, New Jersey. A link to the abstracts and presentations is included here.

Commercial & Recreational Fisheries

American eel are an important resource from both a biodiversity and human use perspective. They serve as an important prey species for many fish, aquatic mammals and fish-eating birds. Although fisheries have significantly contracted from historical levels, eel support valuable commercial fisheries as well as small scale recreational and subsistence fisheries.

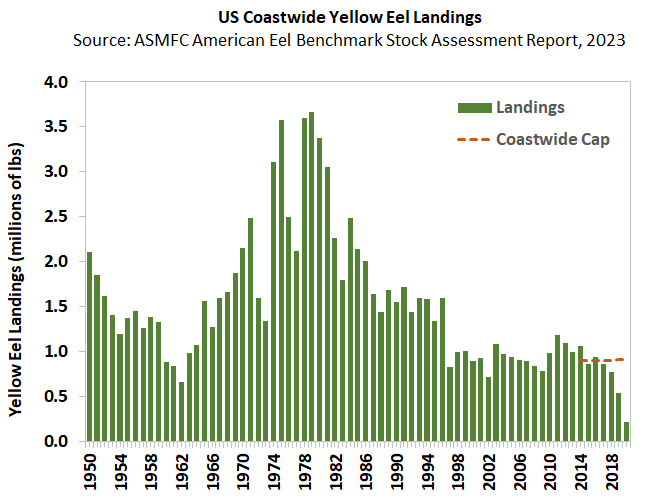

From the 1970s to the mid-1980s, American eel supported significant commercial fisheries, with landings ranging from 2.5 to 3.6 million pounds. Landings dropped to 1.6 million pounds in 1987 and have remained at low levels, ranging from 1.5 million to a low of under 300,000 pounds in 2020. State-reported landings of yellow eels in 2022 totaled approximately 334,653 pounds, which is a 2% increase from 2021 and well below the coastwide cap of 916,473 pounds.

Since 2011, there has been a growing international demand for glass eels (an early life stage of American eel) for aquaculture purposes, which has increased landings and the price per pound of glass eels. In 2022, total glass eel harvest from Maine and South Carolina remained below Maine’s quota of 9,688 pounds.

Recreational harvest has been on the decline since its peak in 1985 at 160,000 eel. Harvest was last estimated to be around 6,000 eel in 2009 (the last year the Marine Recreational Information Program collected recreational data on American eel). Given the small scale of the fishery in recent years, there is limited monitoring of recreational catch by the states.

Stock Status

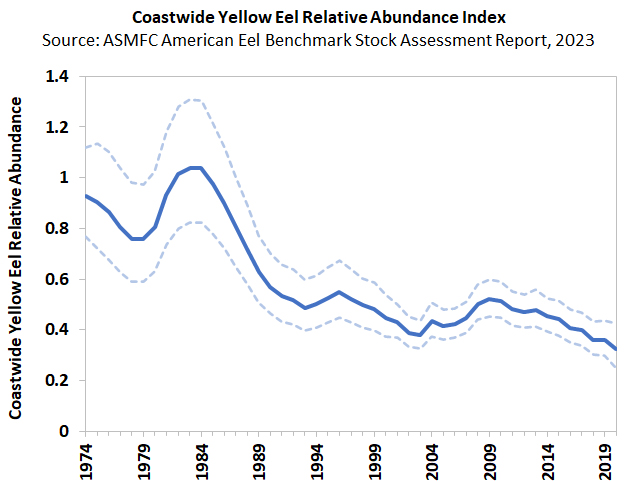

From a biological perspective, much is still unknown about American eel. Information is limited about their abundance, status at all life stages, and habitat requirements. According to the 2023 stock assessment, the American eel population remains depleted in U.S. waters. The stock is at or near historically low levels due to a combination of historical overfishing, habitat loss, food web alterations, predation, turbine mortality, environmental changes, toxins and contaminants, and disease. Based on several trend analyses, abundance the stock is considered depleted, consistent with the findings of the 2012 and 2017 assessments. The 2023 stock assessment found that the yellow eel population was at lower levels than the previous assessment, and yellow eel harvest should be decreased. Trend analyses of abundance indices indicated large declines in abundance of yellow eels during the 1980s through the early 1990s, with primarily neutral or stable abundance from the mid-1990s through 2010, followed by further declines. Total landings remain low but stable. No overfishing determination can be made based on the analyses performed. The results of the 2023 Benchmark Stock Assessment and Peer Review were accepted for management use in August 2023.

In 2011, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) initiated a status review of American eel under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) to assess the health of the population and the magnitude of threats facing the species. On October 7, 2015, USFWS announced that the American eel is stable and does not need protection under the ESA. Nonetheless, for the species’ long-term stability, the agency recommends continuing efforts to maintain healthy habitats, monitor harvest levels, and improve river passage for migrating eels. In 2014, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) listed American eel as “Endangered” on the Red List. The IUCN assesses flora and fauna globally to determine their conservation status (not evaluated to extinct). While the IUCN list has no legal implications, it is an important metric that accounts for a variety of factors including habitat, threats, potential stresses, and research status. Given these findings, and recent actions taken by the Commission and its member states, the Commission remains committed to closely monitoring American eel fisheries and the status of the resource, and making adjustments to the management program as necessary, to ensure stock rebuilding.

Atlantic Coastal Management

American eel are challenging to conserve and manage on a coastwide basis for a number of reasons. During their life-span American eel navigate through and reside in a wide range of habitats, from the oceanic waters of the Sargasso Sea to the brackish waters of coastal estuaries and the inland freshwater river systems. Additionally, throughout this journey, eel exist under a myriad of management authorities, from international to multiple federal, state and local governments. Life history characteristics such as late age of maturity and a tendency to aggregate during certain life stages further complicate conservation efforts.

American eel are managed by the Commission in territorial seas and inland waters along the Atlantic coast from Maine to Florida. Increasing demand for eel by Asian markets and domestic bait fisheries, coupled with concern about declining eel abundance and limited assessment data, spurred development of the first Interstate Fishery Management Plan (FMP) for American Eel in the mid-1990s. The plan, approved in 1999, provided several reasons why heavy harvest pressure may adversely affect American eel populations: (1) American eel have a slow rate of maturation, requiring eight to 24+ years to attain sexual maturity; (2) glass eel tend to aggregate seasonally during migration, making them vulnerable to directed harvest; (3) harvest of yellow eel is a cumulative stress, over multiple years, on the same year class; and (4) all fishing mortality occurs prior to spawning.

In response to the 2012 stock assessment, which indicated that the American eel population in U.S. waters is depleted, the Commission approved Addendum III (August 2013) and Addendum IV (October 2014) to the Interstate FMP with the goal of reducing mortality and increasing conservation of American eel stocks across all life stages. Addendum III established new management measures for both the commercial (glass, yellow, and silver) and recreational eel fisheries, and implements fishery-independent and fishery-dependent monitoring requirements. Addendum IV established a 907,671 pound coastwide quota for yellow eel fisheries, reduced Maine’s glass eel quota to 9,688 pounds (2014 landings), and allowed for the continuation of New York’s silver eel weir fishery in the Delaware River.

In 2018, Addendum IV provisions were replaced by Addendum V, which increases the yellow eel coastwide cap starting in 2019 to 916,473 pounds; adjusts the method (management trigger) to reduce total landings to the coastwide cap when the cap has been exceeded; and removes the implementation of state-by-state allocations if the management trigger is met. Under Addendum V, management action will now be initiated if the yellow eel coastwide cap is exceeded by 10% in two consecutive years. If the management trigger is exceeded, only those states accounting for more than 1% of the total yellow eel landings will be responsible for adjusting their measures. A workgroup will be formed to define the process to equitably reduce landings among the affected states when the management trigger has been met.

Addendum V, implemented January 1, 2019, also slightly modified the glass eel aquaculture provisions. It maintained the 200 pound limit for glass eel harvest but modified the criteria for evaluating the proposed harvest area’s contribution to the overall population consistent with the recommendations of the Technical Committee. Under the revised provisions, the Board approved Maine’s glass eel aquaculture proposal for the 2019 fishing season, allowing for an additional 200 pounds of glass eels to be harvested for development in domestic aquaculture facilities. This amount is in addition to Maine’s glass eel quota.

Addendum VI, approved in April 2024, maintains Maine’s glass eel quota of 9,688 pounds originally established under Addendum IV. The Board also approved Addendum VII in April 2024. Addendum VII responds to the stock assessment findings that the American eel stock is depleted and the yellow eel population has continued to decline. Addendum VII set the coastwide yellow eel harvest cap to 518,281 pounds using an index-based method that provides management advice based on abundance indices and catch information, as well as management goals specified by the Board. It also modifies biological sampling requirements of the annual young-of-the-year survey and the de minimis policy.

Management Plans & FMP Reviews

- American Eel Addendum VII: Commercial Yellow Eel Management and Monitoring Requirements (May 2024)

- American Eel Addendum VI: Commercial Glass/Elver Eel Management (May 2024)

- Addendum V: Commercial Yellow and Glass/Elver Eel Allocation and Management (August 2018)

- Addendum IV (October 2014)

- Addendum III (August 2013)

- Addendum II (October 2008)

- Addendum I (February 2006)

- Interstate Fishery Management Plan for American Eel (November 1999)

Stock Assessment Reports

- American Eel Stock Assessment Overview (Aug 2023)

- American Eel Benchmark Stock Assessment and Peer Review Report (Aug 2023)

- 2017 American Eel Stock Assessment Update (Oct 2017)

- American Eel Stock Assessment Overview (Oct 2017)

- Americal Eel Benchmark Stock Assessment (May 2012)

- Americal Eel Stock Assessment Overview (May 2012)

- Terms of Reference & Advisory Report to the American Eel Stock Assessment Peer Review (Jan 2006)

Meeting Summaries & Reports

Board Proceedings

- 2024 May Jan

- 2023 Oct Aug Feb

- 2021 Oct May

- 2019 Oct Aug

- 2018 Oct Aug Feb

- 2017 Oct Aug Jan

- 2016 Aug May Feb

- 2015 Nov Aug

- 2014 Oct Aug May Feb

- 2013 Oct Aug May Feb

- 2012 Oct Aug May

- 2010 May

- 2009 Feb

- 2008 Aug May Feb

- 2007 Aug Jan

- 2006 Oct May Feb

- 2005 Oct Aug May Feb

- 2004 Nov Aug May

- 2002 Nov

- 2001 Oct Jan

- 2000 Jun

- 1999 Nov Jan

Technical Committee Meeting Summaries & Reports

- 2023 Dec Dec PDT Jun

- 2020 Mar

- 2019 Jul

- 2018 Jul

- 2017 Jul

- 2016 Sep Jul Apr Jan Jan

- 2015 Oct AddIV Implementation Plans Oct ME Life Cycle Survey

- 2014 Oct May

- 2012 Aug

- 2009 Jul Atlantic Coast Diadromous Fish Habitat: A Review of Utilization, Threats, Recommendations for Conservation, and Research Needs Jan

- 2006 Sep

- 2005 Oct

- 2004 Mar

- 2001 Dec

- 2000 May Feb Yoy Sampling Protocol Jan

Advisory Panel Meeting Summaries

- 2024 Apr

- 2023 Sep

- 2021 Apr

- 2019 Dec

- 2018 Jun

- 2016 Jan

- 2013 May

- 2008 Oct Advisory Panel Meeting Summaries Aug Advisory Panel Meeting Summaries

Press Releases

- American Eel Board Approves Addenda VI and VII Addenda Maintain Maine’s Glass Eel Quota and Modify Yellow Eel Management (May 2024)

- States Schedule Public Hearings on American Eel Draft Addendum VII: Draft Addendum Considers Changes to Commercial Yellow Eel Coastwide Harvest Cap (February 2024)

- American Eel Board Releases Draft Addendum VI for Public Comment: Draft Addendum Considers Maine’s Glass Eel Quota for 2025 and Beyond (February 2024)

- ASMFC American Eel Board Accepts Benchmark Assessment & Peer Review Report for Management Use: Two Addenda Initiated for Yellow Eel and Maine Glass Eel Fisheries (August 2023)

- ASMFC Schedules Peer Review for American Eel Benchmark Stock Assessment for late November/Early December (November 2022)

- ASMFC Begins Preparations for American Eel Benchmark Stock Assessment (August 2020)

- ASMFC American Eel Board Approves Addendum V (August 2018)

- States Schedule Public Hearings on American Eel Draft Addendum V (April 2018)

- ASMFC American Eel Board Approves Draft Addendum V for Public Comment (February 2018)

- American Eel Stock Assessment Update Finds Resource Remains Depleted (October 2017)

- ASMFC American Eel Board Approves North Carolina Aquaculture Plan for 2016 (February 2016)

- ASMFC Finds Delaware Out of Compliance with Addendum III to the Interstate FMP for American Eel (August 2015)

- ASMFC American Eel Board Approves Addendum IV (October 2014)

- ASMFC American Eel Management Board Delays Action on Draft Addendum IV until October (August 2014)

- States Schedule Hearings on American Eel Draft Addendum IV (May 2014)

- ASMFC American Eel Board Approves Draft Addendum IV for Public Comment (May 2014)

- Maine Implements First Ever Quota for Glass Eel Fishery (February 2014)

- ASMFC American Eel Board Postpones Action on Draft Addendum IV: Maine Commits to Develop Plan with Industry to Control Glass Eel Harvest (October 2013)

- ASMFC American Eel Board Approves Addendum III and Initiates Draft Addendum IV (August 2013)

- States Schedule Hearings on American Eel Draft Addendum III: RI Changes Hearing Date from April 29 to May 1 (April 2013)

- States Schedule Hearings on American Eel Draft Addendum III (April 2013)

- States Schedule Hearings on American Eel Draft Addendum III (March 2013)

- ASMFC American Eel Board Approves Draft Addendum III for Public Comment (February 2013)

- ASMFC American Eel Board Initiates Development of Draft Addendum III to Improve Conservation and Protection of the Stock (August 2012)

- American Eel Benchmark Assessment Indicates Stock is Depleted (May 2012)

- ASMFC American Eel Board Approves Addendum II (October 2008)

- ASMFC American Eel Board Initiates Addendum to Facilitate Survival of Spawners and Enhance Biomass (February 2007)

- ASMFC American Eel Board Approves Addendum I: Addendum Aims to Improve Data Collection (February 2006)

- Non-Traditional Stakeholders Sought for Participation on ASMFC American Eel Advisory Panel (April 2005)

- ASMFC American Eel Board Calls for Development of Amendment 1 to the Interstate Plan: Plan to Address Continued Stock Declines (March 2004)