Weakfish

Latest News and Resources

-

Population Abundance

Depleted

Fishing Mortality

Overfishing not occurring

Current Status

Stock status based on 2019 assessment update. Species depleted since 2003. Population experiencing high levels of natural mortality, preventing stock recovery. Harvest limited to 1 fish bag limit and a 100-pound commercial bycatch limit. 2025 stock assessment update was not accepted for management use. A benchmark stock assessment is scheduled to begin in 2026.

Meeting Calendar

Next Meeting

No events found

Contacts

- Tracey Bauer, FMP Coordinator (TBauer@asmfc.org)

- Management Board, Doug Haymans, Chair

- Technical Committee, Erin Levesque, Chair

- Advisory Panel

Species Information

Weakfish are cherished game fish found along the Atlantic coast from Nova Scotia down to Florida, with the highest numbers between New York and North Carolina. Known for their delicious taste and spirited fight, weakfish migrate inshore during the warmer months to spawn and thrive in estuarine and coastal waters. Once a staple in both commercial and recreational fisheries, their populations have declined significantly over the past few decades due to overfishing and habitat loss.

Today, most weakfish catches come from states like New York, North Carolina, and Virginia, with recreational fishing making up the majority of the harvest. Despite management efforts such as size limits and catch restrictions aimed at helping their numbers recover, weakfish still face challenges from high mortality rates. Ongoing regulations and conservation measures are essential to ensure that weakfish remain a sustainable and important part of coastal fishing communities for years to come.

Management

In 1985, as a result of population declines and limited biological information, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission developed an Interstate Fishery Management Plan (FMP) for Weakfish. Weakfish are currently managed under Amendment 4 to the FMP and its subsequent addenda (Addendum I-IV). Addendum IV requires states to implement a one fish recreational creel limit, 100 pound commercial trip limit, 100 pound commercial bycatch limit during closed seasons, and 100 undersized fish per trip allowance for the finfish trawl fishery. The Addendum’s measures are intended to reduce the level of harvest without creating a large amount of discards and to poise the stock for recovery should natural mortality decrease in the future.

In 2018, in response to concern regarding potential increases in commercial discards (in Virginia and North Carolina) due to the 100 pound trip limit, the Technical Committee reviewed discard information to determine whether current management is resulting in significant loss to the fishery through increased dead discards. The Technical Committee found that while notable increases in commercial discards were observed in Virginia and North Carolina in both 2016 and 2017, these singular points did not fit any long-term trend of increase and were not high enough to be a significant concern to the resource. The Technical Committee did not recommend any immediate action based on its analyses.

Stock Status

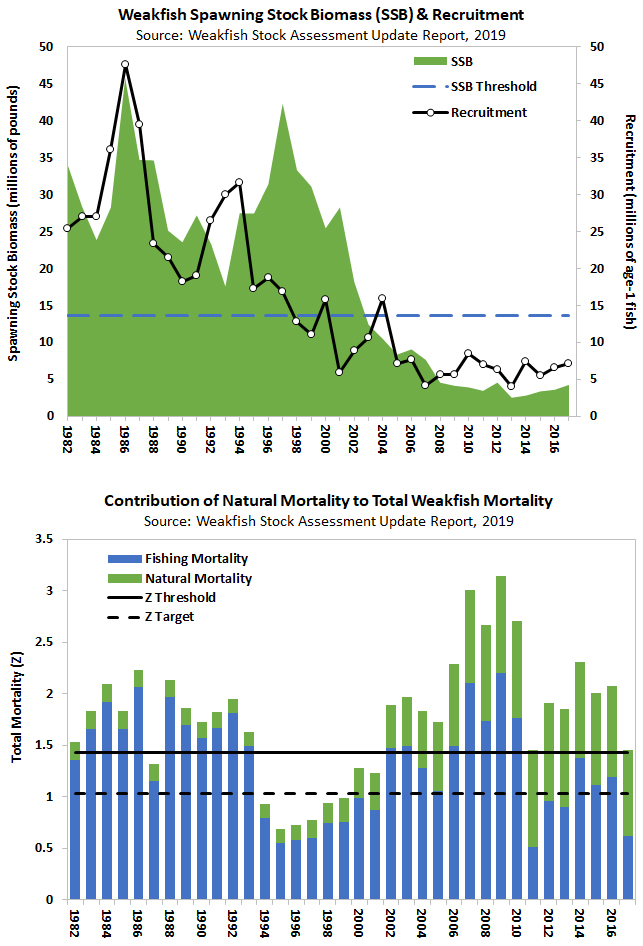

The most recent benchmark stock assessment, conducted in 2016, concluded that the weakfish stock was depleted and overfishing was not occurring (ASMFC 2016). A stock assessment update was completed in 2019 (ASMFC 2019), applying the Bayesian statistical catch-at-age model from the 2016 benchmark assessment to data through 2017. This update also incorporated the new, calibrated estimates of recreational catch by the Marine Recreational Information Program (MRIP).

Estimates of recruitment, spawning stock biomass, and total abundance remained low in recent years. Estimates of fishing mortality were moderately high in recent years, although not near the time-series highs of the mid- to late-2000s, or the earliest years. Natural mortality (e.g., the rate at which fish die due to natural causes such as predation, disease and starvation) remained high, averaging 0.92 in the most recent 10 years, compared to 0.16 over the first 10 years of the time series. Therefore, even though harvest has been at low levels in recent years, the weakfish population has been experiencing very high levels of total mortality (including fishing mortality and natural mortality), preventing the stock from recovering.

Spawning stock biomass in 2017 was estimated at 1,922 mt, below the SSB threshold of 6,170 mt, indicating the stock is depleted. SSB has shown a slight increasing trend in recent years but is still well below the SSB threshold.

Total mortality in 2017 was estimated at 1.45, above both the Z target = 1.03 and the Z threshold = 1.43, indicating total mortality on the stock is too high. Fishing mortality has increased in recent years, but was below the threshold in 2017.

Commercial & Recreational Fisheries

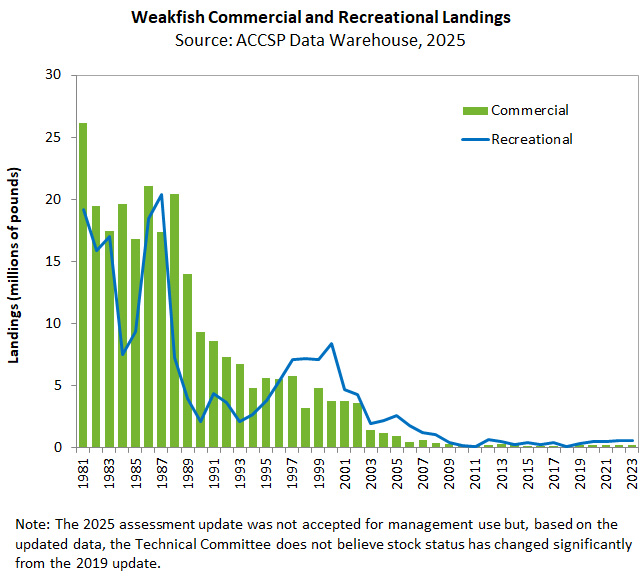

Weakfish have been one of the most important components of a mixed-stock fishery on the Atlantic coast since the 1800s. In the late 1990s, however, weakfish biomass began to decline, reaching an all-time low of 342,990 pounds in 2011 (compared to 45.6 million pounds in 1981). Total landings in the weakfish fishery have generally declined over the past two decades; however, 2021 landings were estimated at 775,535 pounds, a 9% increase from 2021 and the highest value since 2013.

From 1950 to 1970, commercial landings fluctuated without trend, ranging from three to nine million pounds. The early 1970s began a period of tremendous growth in the fishery, with landings peaking at 36 million pounds in 1980. Commercial landings have dramatically declined since the early 1980s, dropping from over 19 million pounds landed in 1982 to 190,176 pounds in 2022. The majority of landings occurred in New York, North Carolina, and Virginia. Commercial fishermen have been known to discard weakfish, especially in the mixed species trawl fishery, and the discard mortality is assumed to be 100%. Discards peaked in the 1990s but have since declined as the result of management measures and a decline in stock abundance.

Recreational landings have followed a similar trend to that of commercial landings. After several harvests above 10 million pounds in the early 1980s, landings decreased to two million pounds by 1989, and hovered between one and two million pounds through the early 1990s. Harvest then increased to over four million pounds by the late 1990s, before exhibiting a decline like that in the commercial fishery. The 2011 recreational harvest also reached a historic low of below 27,081 pounds. Recreational landings in 2022 were 333,904 fish (585,359 pounds) and recreational releases were estimated at 2.8 million fish. Recreational harvest was been dominated by New York, North Carolina, and South Carolina.

Life History

Weakfish (Cynoscion regalis) occur along the Atlantic coast of North America from Nova Scotia to southeastern Florida, but are more common from New York to North Carolina. Warming of coastal waters in the spring prompts an inshore and northerly migration of adults from their offshore wintering grounds between Chesapeake Bay and Cape Lookout, North Carolina to nearshore sounds, bays, and estuaries. Spawning occurs shortly afterwards, peaking from April to June, with some geographical variation in timing. Females continuously produce eggs during the spawning season and release them over a period of time rather than once. In the fall, an offshore and southerly migration of adults coincides with declining water temperatures.

Feeding on microscopic animals, larval weakfish journey from spawning areas to nursery areas, located in deeper portions of coastal rivers, bays, sounds, and estuaries. They remain in these areas until October to December of their first year, after which the juveniles migrate to the coast. Growth in weakfish is especially rapid in the first year and they mature at a young age. Size at age-1 is variable but most fish are 10 to 11 inches long. As adults, weakfish are often found near the periphery of eelgrass beds, perhaps because weakfish feed primarily on shrimp, other crustaceans, and small fish that are found near these grass beds.

News & Resources

Explore recent news, management updates, and scientific reports to gain a deeper understanding of ongoing conservation efforts and sustainability strategies.

-

Prepared for the Commissioner Manual

-

-

A summary of all the board meetings, press releases and motions from the 2025 Summer Meeting.

-

-

Combined materials for all Boards convening at the ASMFC Summer Meeting

-

Consider 2025 Weakfish Stock Assessment Update Possible; Elect Vice-Chair

-

The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission’s Summer Meeting will be August 5-7, 2025 at The Westin Crystal City.

-

Consider 2025 Weakfish Stock Assessment Update Possible; Elect Vice-Chair

-

-

-

-

Get Hooked on ASMFC News

Dive into the latest updates and catch all the important news by joining our newsletter mailing list. Stay in the loop with meeting agendas, fisheries management news, and more.