Tagging Research

Tagging data, essential for stock assessments and understanding fish behaviors, come from activities ranging from conventional tagging to high-tech methods like acoustic telemetry and archival tagging. This page provides an in-depth look at how these techniques help scientists track movement patterns, gather population demographics, and improve sustainability strategies.

Tagging data are valuable inputs to the stock assessments of several species managed by the Commission, including Atlantic striped bass, red drum, Atlantic cobia, Atlantic sturgeon, weakfish, spiny dogfish, and coastal sharks. Conducted properly with clearly defined objectives, tagging can yield a wealth of information, including data about movement patterns, population structure and demographics, mortality rates, and other life history characteristics.

Conventional Tagging Methods

Conventional tagging activities use externally visible tags and rely on the person recapturing the animal to report data, such as date of recapture, disposition (released or harvested), length, and location. By comparing lengths recorded at the time of initial tagging and again during subsequent recapture, researchers can provide information on growth. Length measurements of released fish recorded by recreational anglers also provide information on the size composition of the recreational catch, which is essential for understanding the portion of the population that is affected by discard mortality. The proportion of fish recaptured over different time periods provides information on survival and mortality. Tagged fish that are recaptured also provide scientists with information to better understand habitat preferences, seasonal movements and migrations, and stock boundaries.

Advanced Tagging Techniques

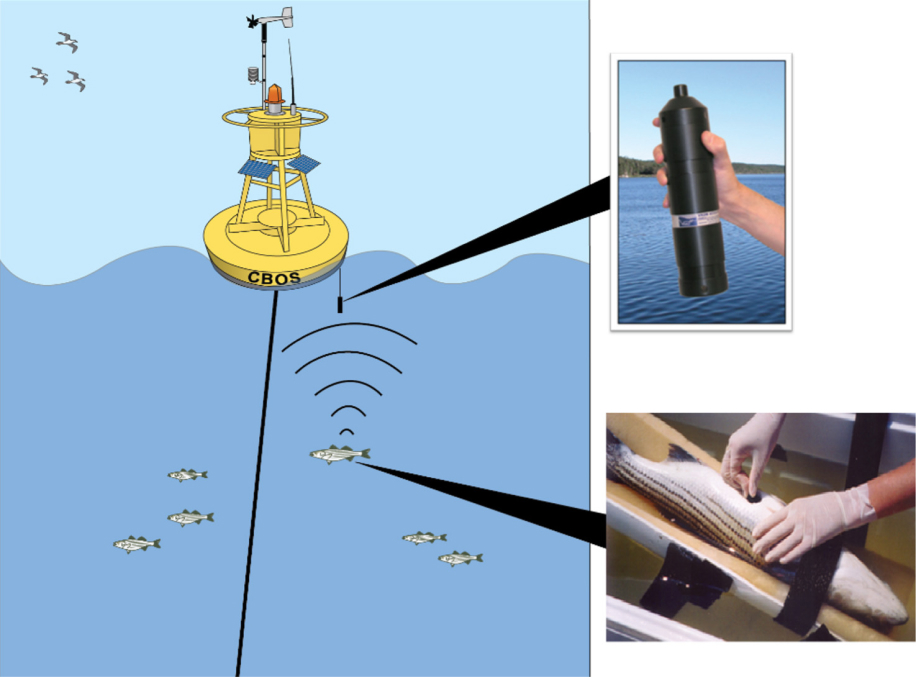

Alternative forms of tagging research are acoustic telemetry and archival tagging, which do not rely on the person recapturing the animal to record data. In these methods, transmitters in the tags are either attached to or surgically implanted in a fish. Acoustic tags, commonly used on fish that remain in one general area, emit a unique sound, or ping, that is passively detected and recorded as the fish passes by receivers. To maximize data collection, researchers strategically set up an array of receivers in the area where the fish are tagged, often also relying on receivers deployed by other researchers. When a tagged fish comes within range, these fixed listening stations record and store the time and unique identification number of the fish. When researchers retrieve the data, they can determine the fish’s movement pattern and if the fish stopped moving, to infer mortality of the fish. However, if the fish moves outside the array of receivers, it essentially disappears, making acoustic tags best suited for species that remain within areas where receivers are deployed.

If researchers want to tag large pelagic fish that travel long distances, like tunas, billfish, and sharks, or track fish in areas without acoustic receiver coverage, they can use an archival tag, which stores data on a computer chip inside the tag. In some cases, the archival tag needs to be physically recovered in the field so researchers can download the stored data from the computer chip to understand the fish’s movement. In other cases, the tags transmit stored data to a satellite, allowing researchers to download the information remotely. Some archival tags can also take readings of environmental conditions like temperature, depth, and light level, which can be compared to movement patterns or survival rates. These tagging activities can provide more detailed information on movement and survival than conventional tagging due to the passive monitoring, but come at a higher cost than conventional tagging.

Interstate Tagging Committee (ITC) and Stakeholder Involvement

To tackle tag-related issues that arise through Commission activities, the Commission established the Interstate Tagging Committee (ITC) in 1999. The goal of the ITC is to improve the quality and utility of tagging data in stock assessments and fisheries management by focusing on outreach, education, and coordination of existing programs. The ITC consists of representatives with expertise in tagging from state and federal agencies and academic institutions.

Tagging programs, typically designed and managed by scientists, rely heavily on stakeholders to run effectively and gather essential recapture information on tagged fish. By reporting tagged fish along with the necessary data and returning high-tech tags, stakeholders such as recreational and commercial anglers, play an important role in the success of tagging programs. Tags come in all shapes, sizes, and colors, ranging from simple streamer tags to sophisticated — and expensive — pop-off archival tags. Different tags are used for different species and purposes.

Tag Identification and Reporting Methods

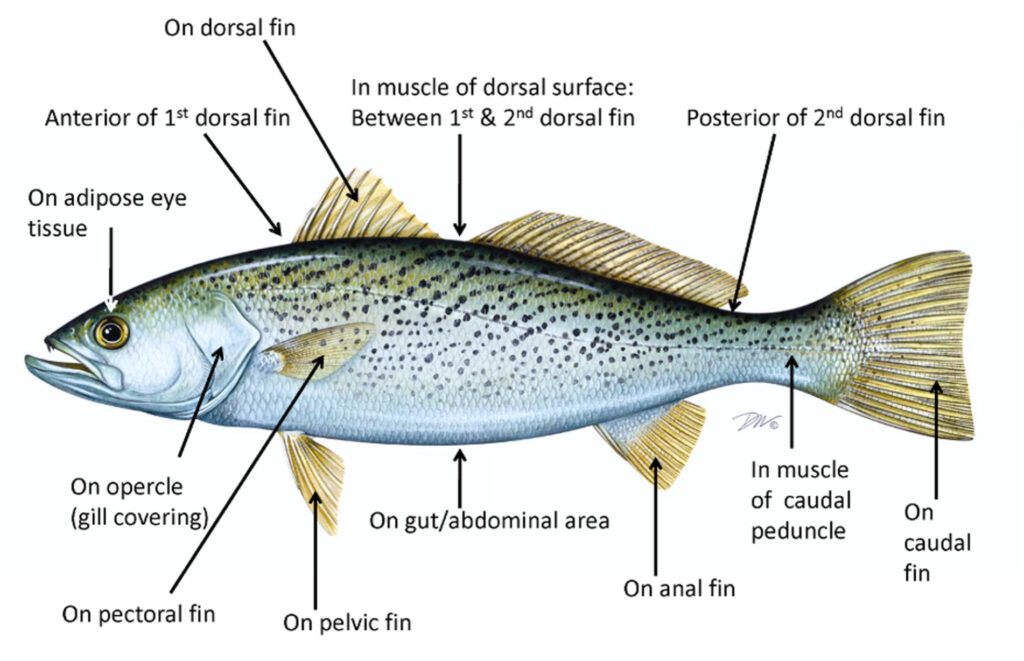

If you catch a fish with a conventional tag, you’ll notice the tag has contact information, such as a phone number or address, along with the unique tag number. These tags can sometimes be difficult to read after being exposed to the ocean environment for a long time. To help with this, the ITC developed a Program Search Tool. This handy tool allows you to search for details about the tagged fish based on the tagging program. Even if the tag is difficult to read, you can use the tool to find the right program by entering information on such as the fish species, tag type and color, and the tags location on the fish. Each program listing includes contact details to make reporting easier.

Once you’ve identified the program, contact them to report the tag and ensure the recapture data is recorded correctly. When you report a tag, many programs will send you information about that fish, such as when and where it was tagged. Some programs even offer rewards for reporting.

You can report a tagged fish whether you keep it, discard it dead, or release it alive. Here are some tips for providing the best information when you report a tag.

- Be alert! Tags are designed to be as unobtrusive as possible, so they don’t change the fish’s behavior. That means that you might not see one if you’re not looking for it.

- Get the tag number. You don’t have to remove the tag if you’re going to release the fish alive, instead, photograph or write down the tag number and the agency name or contact number. If you’re not prepared to obtain that information, or the numbers are illegible, you can cut the tag off without pulling it out. Some tags have their number and contact information printed on them twice, so you can snip off the top half and leave the rest of the tag for the next angler that catches it.

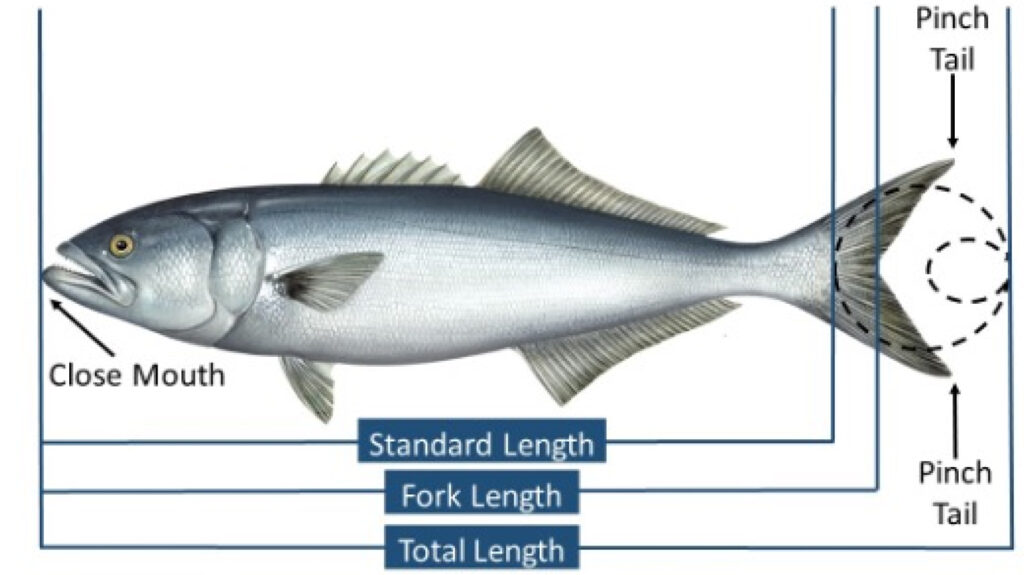

- Measure the fish. A careful measurement is very useful to scientists. When measuring your fish, use one of the standard methods described below. For all methods, when collecting a measurement, be sure to lay the fish down on top of a ruler or tape measure, rather than pulling a tape measure over the fish. All measurements should start at the tip of the snout, but where to end depends on what type of measurement you’re taking. Whichever method you choose, be sure to include the measurement type when you report the tag. You can measure the fish even if you plan to release it alive. Just handle it gently with wet hands or wet gloves, and return it to the water as quickly as possible.

How to Measure

- Standard length: From the tip of the snout to the end of the fleshy part of the tail (the caudal peduncle)

- Fork length: From the tip of the snout to the fork of the tail

- Total length: From the tip of the snout to the end of tail fin, with the lobes of the tail squeezed together

More information is always better, but any information is better than none! Some programs are interested in the condition of the fish (e.g., injured or healthy), what type of gear you used, and other information, but even providing the date and location of where you caught that fish tells scientists a lot. Different programs have varying goals and will want to know different things about the fish you release; here are some common details you can report:

- Species

- Date and location of capture

- Length and type of measurement (standard, total, fork)

- What you did with the fish (kept it, released it alive, discarded it dead, etc.)

- What you did with the tag (removed it or left it on the fish)

Additional Links & Information

- New Acoustic Tagging Study to Evaluate Atlantic Striped Bass Migratory Patterns (Feb/March 2024 Fisheries Focus Article)

- State-run Cooperative Angler Tagging Programs (Nov/Dec 2022 Fisheries Focus article)

Assessments with tag-based analyses:

- 2018 Atlantic Striped Bass Benchmark Stock Assessment (PDF Pg 105)

- 2017 Atlantic Sturgeon Benchmark Stock Assessment and Peer Review Report (Section D, PDF pg 195)

Common Types of Tags

Streamer Tags

These long, thin tags, seen sticking out of the fish’s body and often referred to as dart and anchor tags, streamer tags, or spaghetti tags, are a staple in tagging programs due to their affordability and ease of application. If you join a volunteer-angler tagging program, these are likely the kind of tags you’ll be using. The tags feature a dart-like tip or bar at one end that inserts into the fish’s muscle, securing the tag firmly. Depending on the tag type and its placement, the dart tip can act as an anchor, locking under or between bones to hold the tag more securely.

These tags display a unique number and the contact details of the tagging program. When a fish is tagged, basic information such as the date, location and its size at release are recorded alongside the tag number. When the fish is recaptured, scientists use the tag number to match the initial release information with the recapture data. This process allows scientists to determine how long the fish survived between captures, distance traveled, and growth during that time period.

Disc Tags

Tags should interfere as little as possible with an animal’s behavior and must stay securely attached without adding extra drag. For animals with a shell, like crabs, streamer tags can be difficult to attach and stick out at odd angles. Instead, disc tags are used as these tags lie flat against the body of the tagged animal and can be secured directly to the shell. These tags, pictured on a horseshoe crab, but can be used on fish as well, include contact information and a unique number, just like streamer tags.

Coded Wire Tag or Visual Implant Tag

External tags, such as streamer tags and disc tags, are subject to environmental wear and tear, which can lead to damage or loss. They can also affect an animal’s behavior, especially in smaller fish, or cause injury by rubbing or tearing the flesh where it’s attached. One solution is to use tags that are implanted under the fish’s skin, such as coded wire tags or visual implant tags.

Coded wire tags are tiny metal pieces with microscopic unique codes, typically inserted into a fish’s snout or cheek. They are often used to tag hatchery-reared fish that are released as juveniles into the wild. The fish are very small at this stage and couldn’t handle an external tag. A special tool must be used to detect the presence of a coded wire tag. These fish may also have one or more fins clipped to distinguish them visibly from untagged fish. When the fish is recaptured, researchers can remove the tag and read the number to find out when and where it was released, and verify its age. Since coded wire tags are not visible from the outside of the fish, they are only useful when actively searched for using the required tools.

In contrast, visual implant tags are also implanted internally but are placed very close to the surface, making them visible. These tags are made of a brightly colored, plastic-like substance injected under the skin, usually near the fish’s eye. While some tags may have numbers, many are simply color-coded to represent the year or body of water where the fish were released. Upon recapture, scientists can determine the initial catch location of the “batch” of released fish, but not which individual fish are returned.

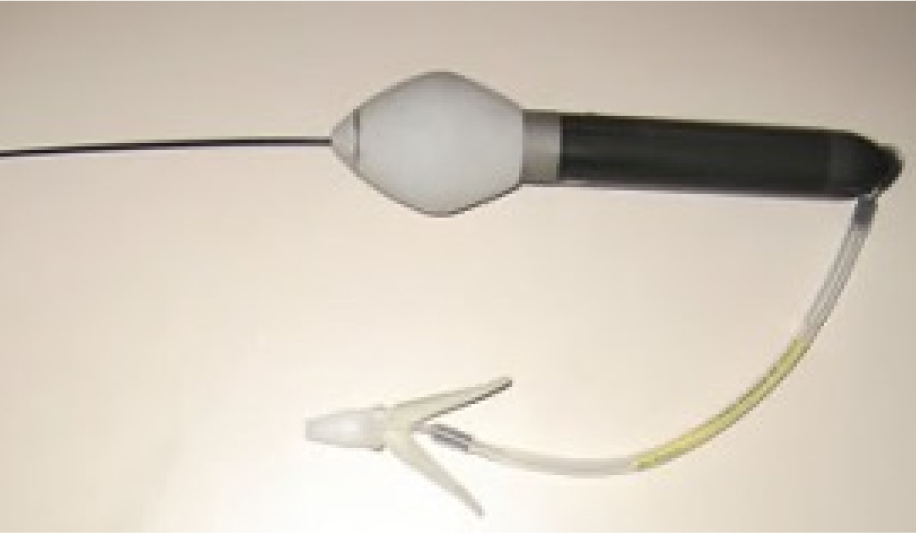

Acoustic Tags

Conventional tags only provide information on where a fish was released and where it was recaptured. To get more detailed information on the movement patterns of tagged fish, researchers use acoustic tags or archival tags. Acoustic tags transmit data to local receivers and should generally be left on any fish that are recaptured and released alive.

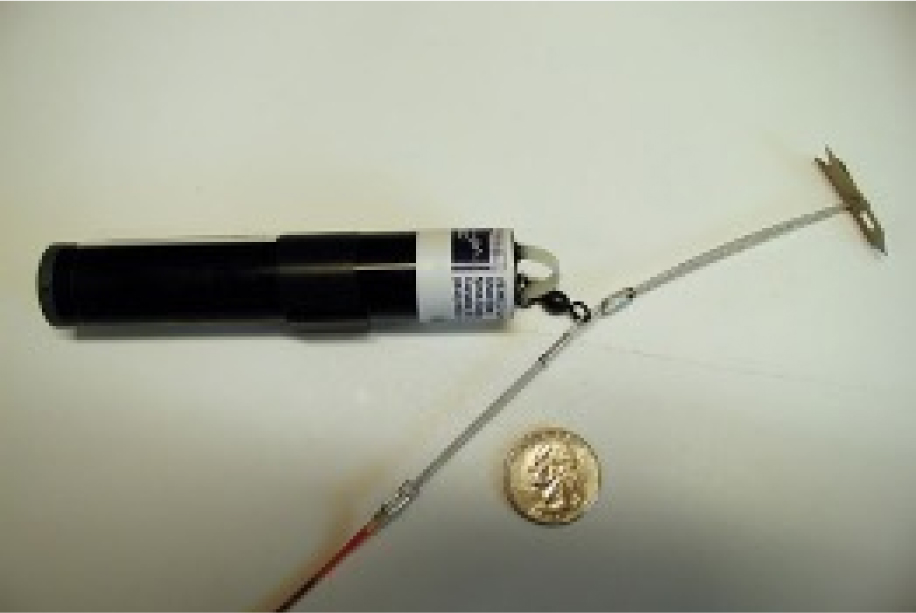

Pop-off Satellite Archival Tag (PSAT)

Archival tags may be implanted internally, sometimes with a light-sensor sticking out, or externally, with some external tags programmed to “pop-off” after a specified amount of time – from a couple of days to several months – and float to the surface.

Given acoustic and archival tags require highly technical methods to implant the tag and “recapture” data are typically collected by receivers or satellites, there are usually few opportunities for stakeholders to participate in these tagging activities. However, pop-off archival tags occasionally wash up on shore, so keep an eye out – as scientists will be very happy to get that tag back. The tag can be reprogrammed and used again.

Atlantic Coast Tagging Programs

There are many existing tagging programs with diverse target species, program structures, objectives, opportunities for participation, and data sharing policies. If you’d like to participate beyond reporting recaptures of tagged fish while fishing, the ITC recommends researching existing programs in your area. Keep in mind that in some states, tagging by non-scientific or non-agency personnel is prohibited or strongly regulated. You can use the ITC’s Program Search Tool to find a tagging program in your area or for the species you’re interested in.

If you administer a tagging program along the East Coast that is not currently included in the ITC Program Search Tool and would like it added, download the registration form (PDF) and return it via email to Jeff Kipp.

Cooperative Angler Tagging Programs

A common tagging program structure along the Atlantic coast is the multispecies angler tagging program. These programs focus on recreationally important species and depend on anglers to report recaptures of tagged fish while fishing. Some of these programs also rely on anglers to apply tags to fish that are going to be released alive while fishing. Several of these programs have been certified by the ITC for meeting criteria to ensure scientific quality and fish safety (see certification process below).

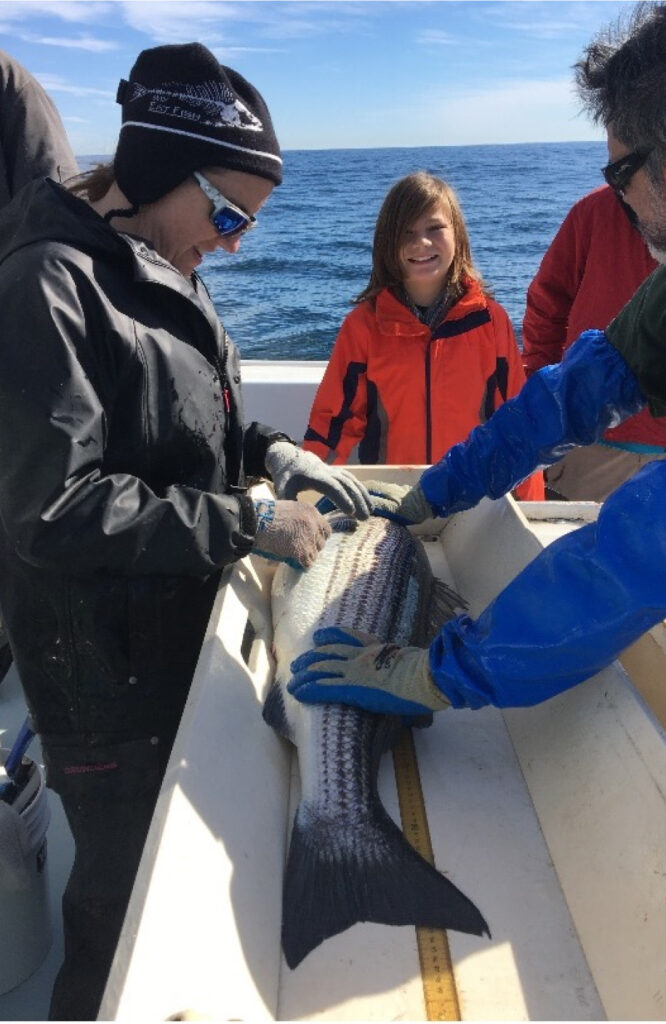

A long-term tagging program that the Commission participates in is the Atlantic Striped Bass Cooperative Tagging Program administered by the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). This cooperative effort includes striped bass tagging programs led by state and federal agencies from North Carolina to Massachusetts. In particular, the Commission participates in the Cooperative Winter Tagging Program conducted by USFWS. The program organizes scientists to conduct field tagging of striped bass aboard a charter boat each winter in nearshore waters of the Mid-Atlantic region. This program then relies on recaptures by stakeholders and agency staff during fishery-independent monitoring programs to generate data used in striped bass stock assessments.

Acoustic Telemetry Networks

Networks have developed to facilitate the sharing of telemetry data and collaboration among researchers, including the FACT Network (https://secoora.org/fact/) and the Atlantic Cooperative Telemetry Network (ACT, https://www.theactnetwork.com/). The ACT Network uses the Mid-Atlantic Acoustic Telemetry Observation System (MATOS, https://matos.asascience.com/) data portal to archive and share telemetry data. Data from telemetry tagging research has improved our understanding of life history and advanced stock assessment techniques of Commission-managed species, including Atlantic sturgeon, Atlantic striped bass, and Atlantic cobia.

Tagging Program Certification Process

A well-designed tagging program can provide valuable information about a species’ life-history and movement patterns, while a poorly designed program can yield unusable, biased results and even harm the fish it is intended to study.

To achieve its goals, the ITC has developed a voluntary certification process for tagging programs. The certification process promotes effective tagging programs that use good tagging practices and facilitates the sharing of tagging information among scientific and fisheries management groups for use in stock assessments and management activities. Programs provide information on their objectives and methods, and experts from the ITC review the information to determine whether the program is scientifically sound and worthy of certification. The ITC also provides feedback to improve program design. All approved programs are listed in the Program Search Tool as certified programs meeting the criteria for scientific quality and fish safety. The ITC encourages all tagging programs to apply.

Organizations interested in having their programs certified should download the certification application (PDF) and submit the completed application and any supporting documentation to Jeff Kipp (jkipp@asmfc.org). One application per tagging program should be submitted regardless of the number of species tagged.

Applications will be sent to the appropriate Commission species technical committee(s) and the certification subcommittee of the ITC for review. The ITC will rate each item (see application for more information on rating system) and respond to the tagging within 90 days of application date in one of the following ways:

- Award certification to the tagging program, accompanied by a certificate and listing on the website as a certified program that meets the criteria for scientific quality and fish safety

- Notify tagging program of areas that need improvement for certification to be granted, such as redirecting the program goals, or putting them in contact with a local scientific or management group with which to share data. These programs are encouraged to respond with clarifications or changes to their program for future certification.

Our Partners

Get Hooked on ASMFC News

Dive into the latest updates and catch all the important news by joining our newsletter mailing list. Stay in the loop with meeting agendas, fisheries management news, and more.